Should PTs Use a New Model for Weight Loss?

By Dr. Sean M. Wells, DPT, PT, OCS, ATC/L, CSCS, NSCA-CPT, CNPT, Cert-DN

For decades the predominant model that dictated weight gain, loss, or maintenance was the energy balance model (EBM). The EBM is rooted in one of the basic laws of thermodynamics. It goes without saying that food contains energy and it is typically measured in a unit known as calories (kilocalories in the dietary world). As a person consumes food it provides energy to do work such as exercise, activities of daily living (ADL), physical therapy, basic living functions, or even sport. Energy can come from recently consumed food or stored energy (e.g. fat, glycogen, or protein) from previously eaten food.

Clinicians often explain weight loss to patients as “calories-in versus calories-out” or CICO, which directly relates to the EBM. In brief, CICO helps rehab professionals to explain to clients the balance between the energy coming into their body versus the energy they expend: too much food coming in and not enough expenditures means weight gain, while too little food or excessive exercise means weight loss. Simple, right?

Well, a new model of weight maintenance has been postulated which focuses on the consumption of carbohydrates and their interaction with hormones. The carbohydrate-insulin model (CIM) asserts that our obesity epidemic has only worsened with greater emphasis on CICO and that we as clinicians ought to focus more on reducing refined carbohydrates. The alternative paradigm proposes that increasing fat deposition in the body—resulting from the hormonal responses to a high-glycemic-load diet—drives a positive energy balance. In other words, consuming highly refined carbohydrates can increase fat deposition and alter hormones that further drive more fat mass gain.

What’s the evidence for this new alternative paradigm and how should it impact Doctors of Physical Therapy (DPT)? Let’s take a quick glance at the data and see what’s really happening.

The CIM model weighs heavily on a notion known as glycemic load (GL). A GL can be calculated based on the quantity and glycemic index (GI) of a food. Thus, a meal with only a few bites of a white bread has a relatively low GL versus a meal with a giant bowl of refined pasta. Starchy vegetables like potatoes and cassava, while not refined, may also deliver a high GL if eaten on their own or in very large quantities.

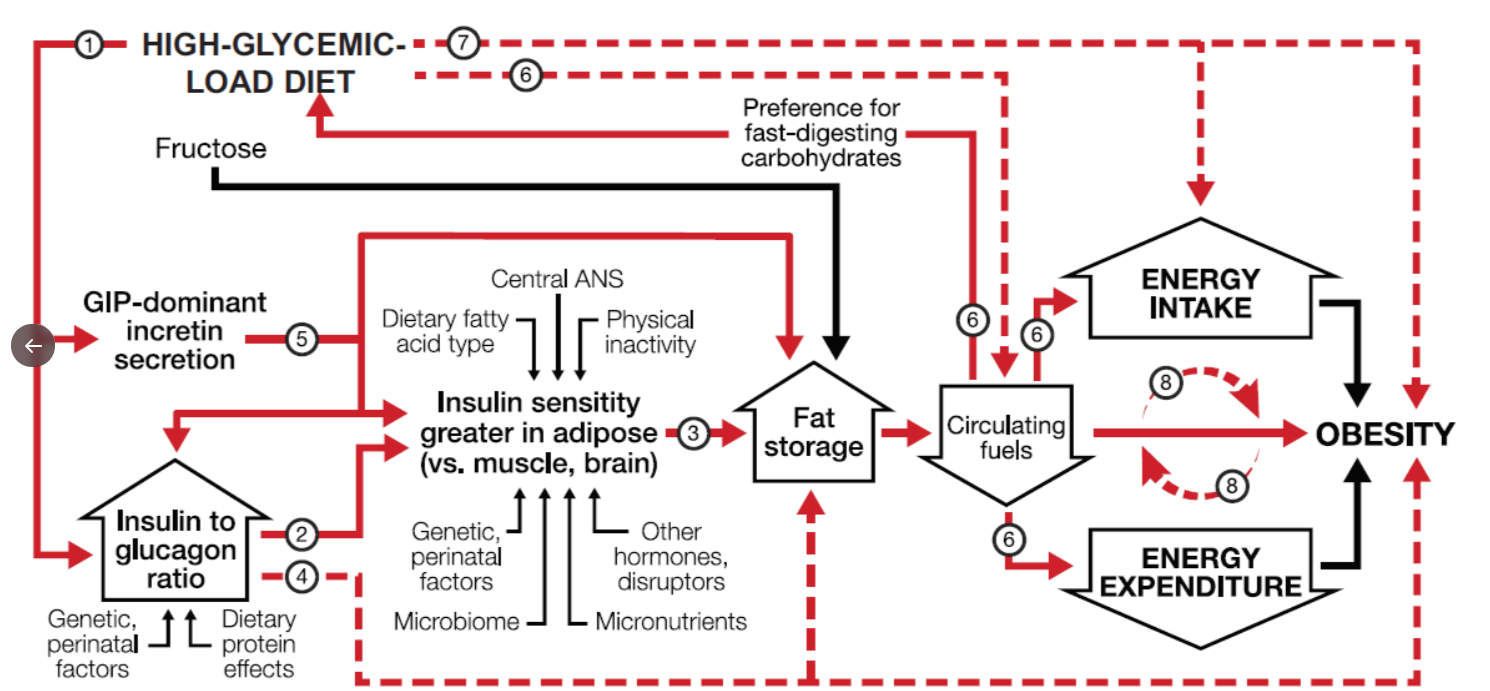

Why does the GL matter? Well, according to the new CIM it is this GL which drives an post-prandial anabolic state. In this anabolic state we see an increase in insulin secretion, suppression of glucagon secretion, and facilitation of a glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP)-dominant incretin response. Initially, after a large GL meal, these hormonal factors help with absorption. However, eventually this strong anabolic state may drive a significant release of glucose from the liver and muscles. Such a release of glucose from the liver and muscles may trigger the central nervous system to activate a hunger response. Studies show that a hunger response from the CNS often drives individuals to seek out rapid energy sources of food (e.g. more refined carbs). And so goes the cycle, purportedly, that a person eats refined carbs → gets hungry → eats more refined carbs with obesity being the end product. Here’s a representation of the CIM from Ludwig et al 2021:

Data to support CIM is still evolving. Authors of a recent review by Ludwig et al provide evidence against EBM, limited evidence supporting CIM via trials, but cite evidence supporting many of the hormonal notions above in animal and lab modeling studies. Ludwig et al do go further by providing arguments against the CIM but with the intention of refuting such arguments. Many of the arguments are sound but leave the reader open with much interpretation as nutrition science has many facets, is multifactorial, and often full of confounding factors.

One big factor I see as a limitation of the CIM is that most dietary guidelines do not support the consumption of highly refined grains. Other organizations, such as the American Heart Association and the American Diabetes Association, put recommended limits on added sugar in much of their literature. The 2020 Dietary Guideline for Americans (DGA), while rife with industry influence, also discourages the consumption of refined grains. As such, our guidance and clinicians already engage and educate clients on reducing their refined carbs and added sugar intake. Palatability of such foods is addressed by Ludwig et al, but I argue that many of these foods are consumed out of convenience, due to lacking food supplies (e.g. food deserts), and/or familial patterning with meals/snacks. I agree with the authors that palatability of foods can be changed -- it takes time, exposure, and education!

Another severe limitation with the publication is the underlying bias of the ketogenic diet. Currently the evidence supports the use of the keto diet for epilepsy. Keto has grown in popularity, partially because of short term weight loss studies and success stories, and the fact that the food can be very tasty (lots of fat!). Adding excessive fat can be detrimental to the gut biome and potentially have other untoward effects (e.g. heart disease from excess saturated fat). Moreover, many keto dieters struggle with bowel movements and micronutrient deficiency due to the lack of fiber and variety of foods. As such, I question whether the authors, such as Gary Taubes, have financial ramifications for publishing a CIM article. Afterall, there are huge financial gains for developing a model for weight loss that helps to support a diet (keto) that is sold in your books, subscriptions, and diet programs.

My final perspective on the CIM is that it still comes back to energy balance. While refined carbohydrates may alter hormones which drive more refined carbohydrate consumption, there still exists the will to change this behavior, eliminate the refined carbs in the diet, and avoid or reduce the weight gain over time. Physios working in wellness or with clients wanting to lose weight should educate their patients to avoid purchasing refined grains and sugars. Have your clients stick with a variety of whole plant based foods and they will feel full thanks to the fiber, lower GL, and small bits of protein. I completely agree, along with many other dietary guidelines, with Ludwig et al in that quality of food matters. However, the food quality does not change the laws of thermodynamics.

In my opinion, we do not have sufficient evidence for PTs and rehab professionals to incorporate the CIM as the best weight loss model available. I think Ludwig et al have detailed a feedback mechanism for why people may repeatedly consume refined foods, which drives a positive calorie balance and weight gain, but they didn’t derive a whole new paradigm for weight loss. The CIM is merely EBM plus a feedback mechanism -- calories in, calories out!

If you like what you see here then know there is more in our 3 board-approved continuing education courses on Nutrition specific for Physical Therapists. Enroll today in our new bundled course offering and save 20%, a value of $60!

Download Your Copy of the Free E-Book:

Learn about the Top 5 Functional Foods to Fight Inflammation and Pain in Physical Therapy.

Keywords: nutrition, diet, continuing education, online, dieting, weight loss, PT, physical therapy, learning, OT, rehab, obesity, lose weight

Image Source: Photo by Andrea Piacquadio from Pexels